(read entire article & comments at San Diego Free Press)

(read entire article & comments at San Diego Free Press)

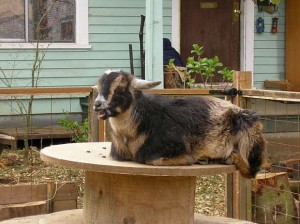

Quieter than dogs, but just as affectionate, goats produce delicious milk and cheese. But they’re not for everyone.

Believe it or not, chickens are not the only farm animals turning up—legally—in cities. Goats are now legal (with some limitations) in Seattle, San Diego, San Francisco, Pasadena, St. Louis, Oakland, Portland, Cleveland, Fort Worth, Berkeley and St. Paul.

But do goats belong in a city? Strangely enough, goats can actually make nice neighbors, so long as their owners have a good fence. But, as a new generation rediscovers agriculture, they are also finding out that raising goats, particularly if you wish to raise them for milk, takes work.

Rachel Hiner and her husband, Andrew Clarke, have had goats for about two years, ever since San Diego changed its rules to allow them. The city allows homeowners to keep two miniature goats, no more, no less—and no bigger. Full-sized goats are still verboten. Males must be neutered, and all goats must have their horns removed, a procedure usually done a few weeks after birth.

Following these rules, Hiner and Clarke got a pair of female goats together with their neighbors, a married couple named Emily and Nick, planning to share the costs, the work and the milk. “The idea of making my own goat cheese sounded magical,” recalls Hiner. And she has made her own cheese. But it also required more work and money than she could have imagined.

They chose Nigerian dwarf goats, the breed of miniature goats most known for milk production. Because the goats are small, they produce a few quarts a day, which is less than larger dairy breeds like Nubian or Alpine. (Another option would be selecting a goat that is a cross between a Nigerian dwarf and a standard-sized dairy breed.)

It was easy to find goats for sale online. The two couples chose two females, an older one they hoped was pregnant (she had been exposed to a buck) and one who was too young to breed. They were named Flora and Fauna, respectively, and together, they cost about $300. Goats who were confirmed pregnant were available too, but they cost more.

As pets, the goats were wonderful. Quieter than dogs, they love being touched and petted by humans, and they can eat fibrous plant material that humans can’t. They will gladly eat out of your hands, although they’ll just as gladly eat your clothes.

The neighbors (mostly) loved them. Erica Tarassoff, a young mother who lives nearby, says, “The exposure is great for the kids.” She enjoys bringing her daughter and her daughter’s friends over to see the goats. Not everyone loves them. Recently, one neighbor complained to the city about the goats. Hiner cannot guess who, as she lists her neighbors on each side of her house, noting that they each like the goats. Tarassoff agrees, saying, “That’s terrible,” that someone complained to the city. She says all the neighbors she knows like the goats.

As milk producers, the goats were initially less successful. Six months passed, and no babies came (a goat’s gestation averages around 150 days). Flora was not pregnant after all. Since only neutered males were allowed in the city, the goats had to go to what Hiner calls “sex camp” on a farm in the country to be impregnated. The studding service cost $170 for two goats. “So right there, that’s a year’s supply of cheese,” Hiner reflects on the price of impregnating her goats. (Costs might be lower in other parts of the country.)

Again, Flora did not get pregnant, but now old enough to breed, Fauna did. She had twins, a boy and a girl, in early 2013. Because the law only allows two goats, they sold Flora and the boy kid, but kept the girl kid, whom they named Pepper. Now it was time to milk Fauna. They bought and assembled a milking stand for about $200. It’s about the size and shape of a bench, and the goat stands on it and puts her head through two bars in order to reach a bowl of treats. To keep her in place, you clip the bars together so she cannot remove her head. Then you milk her as she eats. Fauna, unfortunately, was not always on board with this plan. She sometimes kicked at the person’s hand on her udder, and occasionally landed a dirty hoof in the container of milk. And because Fauna’s teats were small, only the two women who co-owned her had hands small enough to milk her, which meant that milking duties could not be shared four ways. Then there was the matter of competition. The humans wanted the milk, but so did the kids. Even after the male kid was sold to a new home, the female, Pepper, still wanted to nurse. After milking Fauna for three or four months, they gave up.

Now, Pepper is old enough to breed, so Hiner and Clarke are trying again. They just picked up both goats from “sex camp,” and with luck, both are pregnant. They gave up sharing their goats with the other couple, because it was too difficult. The milk was delicious, the cheese was easy to make, and the goats are sweet, but Hiner says, “This might be my last round of goat babies.” Keeping the goats has been an eyeopening experience that has enlightened her to how livestock are routinely treated on farms, and she just does not have the stomach for some of the realities of goat husbandry. “You have to separate the mothers from their babies [or else the babies drink all the milk], and you have to burn the kids’ horns off if they live in the city. If it’s a male you have to castrate it, and then you might sell it to someone who is going to eat it, and I don’t feel good about that. It’s just this whole processes we are being awakened to, because these animals are raised as commodities. I might stop eating cheese. I gave up meat because of it.”

To be sure, some urban goat owners make it work. It’s easy to find success stories online, like one from a woman in Chicago, and Jennie Grant in Seattle, who wrote the book City Goats: The Goat Justice League’s Guide to Backyard Goat Keeping. But would-be goat owners should enter into the experience with their eyes open.

On the other hand, cities worried that goats make bad neighbors should learn from the several cities that now allow them. As Rachel Hiner points out, her neighborhood is full of nuisances that are far more obnoxious than her goats—weed whackers, airplanes flying overhead, a flock of extremely noisy wild parrots, and even some dogs. Yet nobody considers banning these.