Major roadway once planned through Maple Canyon

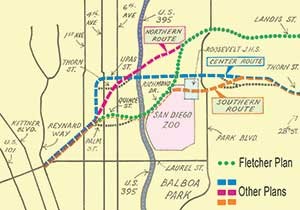

In 1957 the city began to study a new four-lane east-west road to eliminate use of Laurel Street through Balboa Park and relieve traffic congestion in Hillcrest. Years of studies were financed, resulting in nothing. By late 1962 the Quince-Morley Group, a neighborhood organization, hired engineer Glenn Rick to explain three proposals, cleverly identified as the Northern, Center and Southern routes. Each would begin near the foot of Laurel Street at State and run northeast through Maple Canyon.

At a point near Second Avenue the northern and center routes would swing north and cross Highway 163 (then US  395) near Upas. The southern route would cross 163 at Quince and join the center route just east of Park Boulevard, ending at Upas or Thorn. The Quince-Morley Group favored this plan. The northern route would cross Robinson at Park Boulevard then continue east on Landis Street through the Morley Field area. All three highways required utilization of some Balboa Park land; the Upas Street route would pass adjacent to the George Marston House.

395) near Upas. The southern route would cross 163 at Quince and join the center route just east of Park Boulevard, ending at Upas or Thorn. The Quince-Morley Group favored this plan. The northern route would cross Robinson at Park Boulevard then continue east on Landis Street through the Morley Field area. All three highways required utilization of some Balboa Park land; the Upas Street route would pass adjacent to the George Marston House.

Much to their dismay, residents learned that their most favored southern route would require a tunnel and cost nearly $4,000,000 more than originally proposed. The engineer suggested that the center route might also require a tunnel. The city didn’t want to spend the money and preferred the northern route, exiting the canyon at Quince northbound on Third.

State highway engineer Jacob Dekema reported thatafter the Maple Canyon route was built, two roads would be constructed along both sides of El Prado between the Cabrillo Bridge and Park Boulevard to clear the main road of autos. Two other Balboa Park highway projects were also planned (but thankfully not completed) — (1) widening 163 to six or eight lanes and (2) a freeway through Switzer Canyon.

In 1963 the Park & Recreation Committee unanimously recommended the northern option, but the city manager recommended a new alternative. The “Fletcher Plan” combined the south and north routes, which he thought would get the least amount of public objections. Thomas Fletcher wanted a pair of one-way roads on Quince and Palm streets across Sixth Avenue into Balboa Park, which would join Richmond Street near the 163 off ramp then cross Upas Street and connect to the northern route near the northeast end of Marston Canyon.

Emerging from Park Boulevard the route would push due east along Landis Street. This latter section would require the most expensive acquisition of right-of-way in the residential area, and remove 4.6 acres of Balboa Park compared to as much as 12 acres in other proposals. Additionally, Fletcher’s plan would require hearings by the Planning Commission and the City Council because it meant a change to the Balboa Park master plan. The council rescinded its initial approval of Fletcher’s plan after residents complained that they were not advised of the hearing where approval was given.

By mid-1964 the assistant city manager recommended a three-phase program in lieu of the Maple Canyon Road including increased street capacity in Hillcrest and ending curb parking along University at rush hours. Additionally, it called for a redesign of Washington Street and 163 off ramps; develop Sixth and Seventh avenues as one-way pairs and coordinate plans with the Hillcrest Business Association.

In September 1964 at the urging of Park West businessmen and the Balboa Park Protective Association (now The Committee of One Hundred) the City Council revisited the Maple Canyon Road project. The Fletcher Route was resurrected and unanimously rejected by the Park & Recreation Board…however the Planning Commission unanimously recommended it. In November the City Council listened to two hours of testimony and ultimately deferred their decision.

Opponents didn’t want encroachment into the park. Speaking on behalf of the West Balboa Park Property Owners W.E. Wessels said, “People were here before cars. We have inherited this park and should be guardians of it.” Dorothea Edmiston, president of Citizens Coordinate said, “We want this council to go down in history as the one that saved Balboa Park.”

In December 1964 the City Council ended two years of controversy and finally approved the Maple Canyon Road setting aside $2,000,000 to begin work in the fiscal year, but the work was never started, and sometime after 1969, the plans were abandoned. By 1981 the city had dedicated Maple Canyon as open space and began efforts to acquire the remaining privately owned parcels in this beautiful canyon.